A commentary on potential reparations claims arising from the Russia-Ukraine conflict

15th May 2024

During Paris Arbitration Week, HKA hosted a panel that considered the options for compensation for damages loss or injury open to victims of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The panel was timely as the Register for Damage for Ukraine (“the Register” or “RD4U”) was on the point of opening (and now has opened) for the receipt of certain claims. The Register which sits in the Hague was established within the framework of the Council of Europe (and with support of others including the USA and Canada) to provide a structure for recording claims for compensation arising from the invasion. The Register is precisely that: a register to provide a permanent record of the loss and injury suffered. Its mandate does not extend to assessing the validity or value of claims or order any compensation payments.

This will therefore necessarily be part of a wider compensation mechanism the form of which has yet to be decided – although one could contemplate some form of compensation commission and fund perhaps not dissimilar to the United Nations Compensation Commission (“UNCC”) process following the First Gulf War. Under that process, 6 categories of claim were established labelled A (individual harm) to F (government). Claims were submitted to the UNCC in Geneva and assessed by them with payments made from a fund established using a percentage of Iraq’s oil revenues, The UNCC’s work was substantially concluded by 2005 – some 14 years after the war- with awards totalling over $52bn to over 1.5million successful claimants. This was of course only possible with the agreement of Iraq to the funding process.

The UNCC process was also a paper heavy exercise. Thanks in part to changes in technology, the Register will record claims solely in digital form. There will also be a direct interface between the register and the Ukrainian mobile application “Diia”. To date the Register is open for one category of claim: Category A3.1 – Damage or destruction of residential immovable property. To date over 1000 claims have already been registered.

In addition, understanding the role and scope of the Register the panel also discussed the other options through which potential claimants could seek compensation. It was noted that Russia is party to more than 60 bilateral investment treaties which remain in force. Clearly these provide protections through the guarantee of fair and equitable treatment and from unlawful expropriation. Discussion of these other options is beyond the scope of this article, other than to note that a number of claims have been filed both in relation to the full invasion in 2022 but also in relation to the earlier occupation and annexation of the Crimea. Many of these latter claims are well advanced – and have found in favour of the claimants – although Russia failed to participate in them for much of the past several years. Naturally the ability to enforce any successful claims was a topic of interest (and uncertainty).

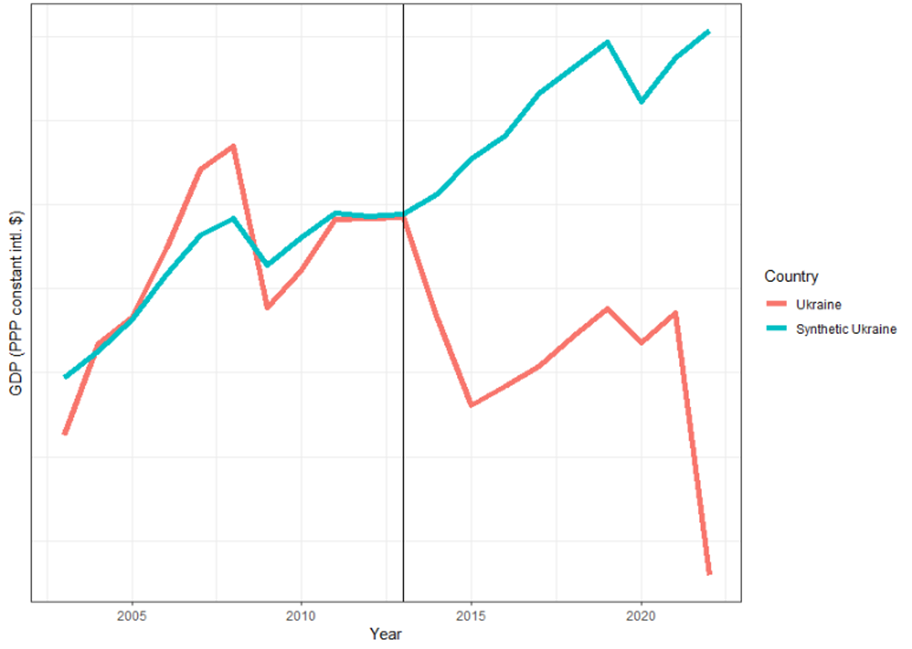

HKA contributed to the panel by undertaking a top down assessment of the economic impact of the conflict on the Ukrainian economy. To do this, requires an understanding of the evolution of Ukrainian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) but for the conflict. Given that this counterfactual scenario cannot be observed, it has to be estimated.

The synthetic control method is used extensively in economic literature to assess the causal impact of events and policy interventions. In the past, synthetic controls have been used to estimate the impact of German unification in 1990 on the German economy,[1]Alberto Abadie et al., (2014) Comparative politics and the synthetic control method, American Journal of Political Science, Vol 59, No 2, 495-510. Available here: Comparative Politics and the … Continue reading and the impact on the UK economy of leaving the EU.[2]John Springford, (2021) The cost of Brexit, Centre for European Reform. Available here: insight_JS_costbrexit_sept_29.11.21.pdf (cer.eu).

The synthetic control method uses data on a group of comparator countries[3]These comparator countries are chosen such that the risk of spill overs from the Russia-Ukraine conflict is minimised. to construct a counterfactual Ukraine GDP that evolves in a similar manner to Ukraine GDP prior to the conflict. Information on these comparator countries is then used to estimate GDP for Ukraine in absence of the conflict. The set of comparator countries we used were Eastern European countries other than post-Soviet states. Information on inflation, trade activity, and the proportion of children in secondary education is also used to improve the predictive accuracy of the estimated counterfactual.[4]This is consistent with the method deployed by Abadie (2014) to estimate the impact of German unification on the German economy. Looking backwards, the model maps Ukrainian GDP before 2014 to within 5% of the actual outturn.

Figure 1 below shows the results of the analysis both before and after 2014. The figure shows Ukrainian GDP from 2003 to 2022 and counterfactual Ukraine (labelled Synthetic Ukraine) from the same period. The decline of the Ukrainian GDP in 2014 coincides with the annexation of Crimea and the war between pro-Russian separatists and Ukraine in the Donbas region of Ukraine in the same year.[5]World Bank. 2014. Ukraine Economic Update. Available: Balkans Poverty Reduction Forum: Advancing National Strategies (worldbank.org). The model also demonstrates that but for the annexation and subsequent invasion the Ukrainian economy will have continued to grow broadly in line with economies in Central and Eastern Europe.

Figure 1: Ukrainian GDP in absence of the Russia-Ukraine conflict

Notes: The series labelled ‘Synthetic Ukraine’ is an estimate of the counterfactual Ukrainian GDP in absence of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. This estimate is obtained using the synthetic control method. The vertical line indicates the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2014.

Source: HKA calculations

The results show that from 2014 to 2022, Ukraine lost $1.46 trillion in GDP as a result of the conflict. In 2022, itself (the year Russia invaded) the results show a loss of $323 billion. In 2023, the results show a loss of $116 billion. That lost output is lower in 2023 reflects slower growth, and, in some cases, a contraction in economic activity across comparator European countries.

Conclusion

As of today, the war shows little sign of ending. Critical questions of course remain as to how any reparations process might develop. These include the scope of claims, the measurement of damage inflicted and how compensation is to be sourced and paid.

However, the Register now exists with a Board and operational secretariat – and claims are beginning to be recorded. ISDS claims are also advancing. Claims are of course developed on an accounting based approach based on lost profits of individual companies and individuals, i.e. a “bottom up” approach.

In contrast, the analysis presented above assesses the total of lost economic activity and not just lost assets and profits. The reconciliation of these two approaches appears to be central to the quantum of any post war restitution damages. However, it is perhaps instructive that through our analysis we estimate that to date, lost economic activity is already in the order of $1.57 trillion. Evidently, this is increasing daily.

About the Authors

Chris Williams is an economist with over 30 years of experience. He has been appointed as an expert on more than 75 occasions. Chris has provided expert evidence and testimony on more than 30 occasions to international arbitration tribunals (investor state and commercial) as well as high courts, competition courts, and judicial and parliamentary review proceedings across multiple jurisdictions. He has been engaged in major disputed matters, with projects where the disputed value is in excess of $10 billion.

Andrew Flower is a forensic accountant with 30 years of experience in dispute work. He has been appointed as an expert on hundreds of occasions. He has testified in litigation and in international arbitrations (both commercial and investor state) around the world. He has provided written and oral evidence on matters under the auspices of many of the arbitral institutions including the ICC, ICDR, ICSID, DIAC, NAI, DIS, OIC, and under UNCITRAL rules.

Olesya Prantyuk is a Chartered Certified Accountant with more than 15 years of experience in finance and accounting, including over 9 years of experience in disputes. She has been appointed as an expert on 4 occasions (one High Court litigation and three commercial arbitrations) and has assisted the named expert on more than 40 occasions in matters of forensic accounting and commercial damages.

References

| ↑1 | Alberto Abadie et al., (2014) Comparative politics and the synthetic control method, American Journal of Political Science, Vol 59, No 2, 495-510. Available here: Comparative Politics and the Synthetic Control Method (stanford.edu). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Springford, (2021) The cost of Brexit, Centre for European Reform. Available here: insight_JS_costbrexit_sept_29.11.21.pdf (cer.eu). |

| ↑3 | These comparator countries are chosen such that the risk of spill overs from the Russia-Ukraine conflict is minimised. |

| ↑4 | This is consistent with the method deployed by Abadie (2014) to estimate the impact of German unification on the German economy. |

| ↑5 | World Bank. 2014. Ukraine Economic Update. Available: Balkans Poverty Reduction Forum: Advancing National Strategies (worldbank.org). |

This publication presents the views, thoughts or opinions of the author and not necessarily those of HKA. Whilst we take every care to ensure the accuracy of this information at the time of publication, the content is not intended to deal with all aspects of the subject referred to, should not be relied upon and does not constitute advice of any kind. This publication is protected by copyright © 2024 HKA Global Ltd.