Arbitration clause separability re-visited in the court of appeal

4th April 2023

It has long been established in English law that an arbitration agreement may be separable from the principal contract of which it forms or formed part (Heyman v Darwins Ltd. [1942] AC 356).

The principle received statutory recognition over a quarter of a century ago. Section 7 of the Arbitration Act 1996 provides:

“Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, an arbitration agreement which forms or was intended to form part of another agreement (whether or not in writing) shall not be regarded as invalid, non-existent or ineffective because that other agreement is invalid, or did not come into existence or has become ineffective, and it shall for that purpose be treated as a distinct agreement.”

While the principle of separability is well established, disputes do still arise concerning the circumstances in which an arbitration agreement may survive an invalid, ineffective or otherwise non-existent principal contract.

The Court of Appeal has recently provided further guidance on the issue in DHL Project & Chartering Limited v Gemini Ocean Shipping Co Limited [2022] EWCA Civ 1555. In that case the Court of Appeal upheld the first instance judgment of Mr. Justice Jacobs in the Commercial Court, where DHL’s application to set aside an arbitration award of approximately $283,000 plus interest and costs under section 67 of the Arbitration Act 1996 was accepted on the basis that the tribunal did not have substantive jurisdiction because there was no concluded arbitration agreement.

Background Facts

The parties were negotiating the terms of a charter of the bulk carrier ‘Newcastle Express’ for a voyage to China with a cargo of coal in August 2020.

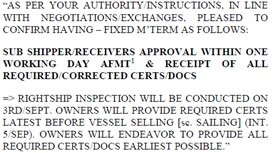

On 25 August the broker circulated a “Main Terms recap”. It is common ground that the recap accurately reflected the state of the negotiations thus far. It began as follows (with original bold text):

Clause 2 of the recap provided, amongst other things, that the vessel should be “RIGHTSHIP APPROVED” and that “prior to charterers lifting their subjects”, Gemini would provide figures for bunker consumption and speed along with a detailed itinerary. Clause 17 contained an arbitration clause.

Gemini intended that the vessel would be inspected on 3 September by Rightship, a vetting system that is widely used for identifying vessels suitable for the carriage of coal and iron ore.

However, by 3 September, Rightship approval had not been obtained. DHL advised the same day that it was not accepting Newcastle Express and that it was released.

There was no issue that, at that time, DHL had not “lifted” the “subject” of “shipper/receivers approval”. Nevertheless, Gemini contended that a binding charterparty had been concluded containing an arbitration clause, and that, by releasing the vessel in the way it did, DHL had repudiated the contract.

Gemini commenced an arbitration against DHL, which proceeded without any involvement by DHL due to an administrative misfunction. The sole arbitrator appointed by Gemini subsequently made an award in favour of it.

The Court of Appeal’s Analysis

Lord Justice Males gave the leading speech. In deciding that Jacobs J was correct in deciding that the arbitrator acted without jurisdiction, and in dismissing Gemini’s appeal, Males LJ derived the following key principles from the authorities he reviewed:

- Two situations need to be distinguished. The first situation is where the dispute is whether a party ever agreed to a contract containing an arbitration clause, that is to say where the argument is that “I never agreed to that” or “our negotiations never got as far as a binding contract”. That is an issue of contract formation, concerned with issues such as offer and acceptance and intention to create legal relations. The second situation is where the parties did assent to the terms of the contract containing an arbitration clause, but their agreement is invalidated on some legal ground which renders the contract void or voidable. That is an issue of contract validity. The parties did agree, but one of them is contending that the agreement is invalidated.

- Where the issue is a matter of contract formation, it will generally be fatal to the arbitration clause: the argument “I never agreed to that” applies to the arbitration clause as much as it does to any other part of the contract. But where the issue is a matter of contract validity, that will not necessarily be so. It is necessary to pay close attention to the precise nature of each dispute in order to see whether the ground on which the main contract is attacked is one which also impeaches the arbitration clause.

- In any event, there must still be ‘an arbitration agreement’. This is apparent from the definition in section 6(1) of the 1996 Act:

“In this Part an ‘arbitration agreement’ means an agreement to submit to arbitration present or future disputes (whether they are contractual or not).”

This refers to an agreement which is legally binding. It follows that the same term in section 7 of the 1996 Act must also refer to an arbitration agreement which is legally binding, and therefore one that satisfies principles of contract formation. Where there is no binding arbitration agreement to begin with, there is nothing to which the separability principle may apply. - The absence of a concluded main contract does not necessarily mean that an arbitration agreement is also non-existent. Rather, the separability principle means that the question of contract formation must be asked twice, once in relation to the main contract and again in relation to the arbitration agreement. In most cases the same answer will be given to both questions, although it is theoretically possible for parties to conclude a binding agreement to arbitrate even if they have not (or not yet) agreed on the main contract. But in both cases the issue is one of contract formation, in particular whether, applying usual principles, the parties have evinced an intention to be bound.

Males LJ summarised his application of the legal principles to the facts of the case as follows:

- The use of ‘subjects’ in charterparty negotiations is a conventional and well-recognised means of ensuring that no binding contract is concluded, and (at least in many cases) is equivalent to the expression ‘subject to contract’…

- The ‘subject’ in the present case was a pre-condition whose effect was to negative any intention to conclude a binding contract until such time as the subject was lifted.

- As a result, either party was free to walk away from the proposed fixture at any time, and for any reason, until the subject was lifted, which it never was.

- The negativing of an intention to conclude a binding contract applied as much to the arbitration clause as to any of the other clauses set out in the recap…

- These conclusions are unaffected by the separability principle. That principle applies where the parties have reached an agreement to refer a dispute between them to arbitration, which they intend (applying an objective test of intention) to be legally binding. It means that a dispute as to the validity of the main contract in which the arbitration agreement is contained does not affect the arbitration agreement unless the ground of invalidity relied on is one which ‘impeaches’ the arbitration agreement itself as well as the main agreement. But it has no application when, as in the present case, the issue is whether agreement to a legally binding arbitration agreement has been reached in the first place.

- What the parties agreed in their negotiations in the present case was that, if a binding contract was concluded as a result of the subject being lifted, that contract would contain an arbitration clause. Nothing more. It is misleading to say that they entered into an arbitration agreement merely by acknowledging that any contract concluded between them would contain such a clause.”

This publication presents the views, thoughts or opinions of the author and not necessarily those of HKA. Whilst we take every care to ensure the accuracy of this information at the time of publication, the content is not intended to deal with all aspects of the subject referred to, should not be relied upon and does not constitute advice of any kind. This publication is protected by copyright © 2024 HKA Global Ltd.