SEC rulemaking necessitates updating incident response plans

29th June 2022

The Comment Period for the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (“SEC”) recently announced cybersecurity disclosure rulemaking is rapidly closing. Investment advisers and funds, public companies and their critical supply chain partners are assessing the potential impacts and preparing themselves for implementation. Whatever the final form, the proposed SEC rulemaking will significantly influence cybersecurity risk management, governance, board oversight and compliance programs. This action also signals a change in regulatory tenor and elevates cybersecurity to a new level of accountability and transparency. This approaching reality necessitates that firms prepare for additional scrutiny of cyber security practices – especially in how they prepare for and manage cybersecurity “incidents.”

The Proposed Rules

The SEC hopes investors will better understand such risks and incidents and be better informed in their investments and voting decisions. As a result, “consistent, comparable, and decision-useful disclosures” regarding cybersecurity risk management, strategy, governance, and incident response to material cybersecurity incidents are proposed.ii

The proposed rules would require current and periodic reporting of “material” cybersecurity incidents; reporting on a registrant’s policies and procedures to identify and manage cybersecurity risk, the impact of cybersecurity risks on the registrant’s business strategy; management’s role and expertise in implementing the registrant’s cybersecurity policies, procedures, and strategies; and the board of director’s oversight role and level of cybersecurity expertise.

“The proposed rules would require current and periodic reporting of “material” cybersecurity incidents…”

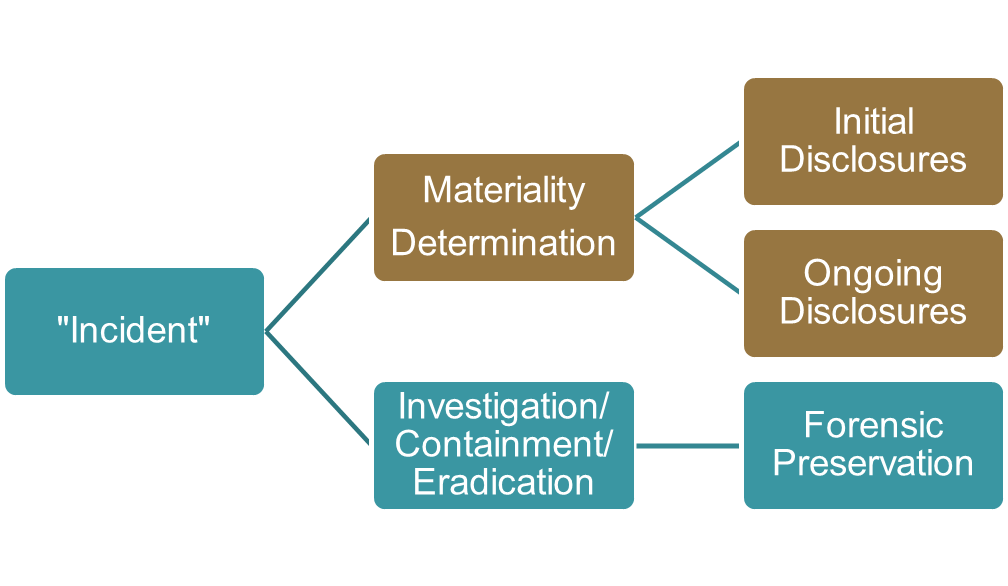

Impact on Incident Response

The proposed rules require a registrant to disclose information about a cybersecurity incident within four business days after they determine that a material cybersecurity incident has occurred. [N.B. This requirement differs from many of the States’ reporting requirements and those of the Strengthening American Cybersecurity Act of 2022.iii] Materiality is to be determined as “reasonably practicable after discovery of the incident” using existing securities case lawi. The SEC considers disclosed information to be material if “there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable shareholder would consider it important” in making an investment decision, or if it would have “significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.”ii There is also a provision to report when an aggregation of prior non-material incidents becomes collectively “material.”

The SEC seeks to define an incident as “an unauthorized occurrence on or conducted through a registrant’s information systems that jeopardizes the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of a registrant’s information systems or any information residing therein.”ii The SEC continued to define “Information Systems” as “information resources, owned or used by the registrant, including physical or virtual infrastructure controlled by such information resources, or components thereof, organized for the collection, processing, maintenance, use, sharing, dissemination, or disposition of a registrant’s information to maintain or support the registrant’s operations.”

As stated by the SEC, a deliberate attack to execute data theft or alteration, or the accidental exposure of data from internal personnel, may lead to material incidents. Material incidents may include, but are not limited to:

- “An unauthorized incident that caused degradation, interruption, loss of control, damage to, or loss of operational technology systems;

- An incident in which an unauthorized party accessed, or a party exceeded authorized access, and altered, or has stolen sensitive business information, personally identifiable information, intellectual property, or information that has resulted, or may result, in a loss or liability for the registrant;

- An incident in which a malicious actor has offered to sell or has threatened to publicly disclose sensitive company data; or

- An incident in which a malicious actor has demanded payment to restore company data that was stolen or altered.”ii

Following an initial disclosure of a material incident, the registrant is obligated to provide periodic updates regarding their reported incident. The duration of periodic updates is contingent upon the material changes, additions, or updates that have been provided during a reporting period.

There is also a provision to disclose when the aggregation of prior non-material incidents is determined collectively to be a “material” incident.

How Will This Impact Incident Response Programs?

The “good news” is that the SEC thinks this will only add another 30 or so hours of work for each registrant, and 25% of that would be performed by external parties. That is quite an optimistic assessment. We estimate that registrants will be dealing with hundreds of hours in modifying processes and hundreds of hours more for each incident.

Here’s why. Incident Response programs are inherently focused on quickly identifying a threat and eliminating it. Second, efforts to understand the scope of data accessed or exfiltrated is needed. Now, a third leg will require immediate consultation with legal counsel knowledgeable on security law cases to make a “materiality” determination. Next, the compliance and investor relations teams will kick into gear. Then, the communications team will prepare for the onslaught ensuing as soon as your filing is made. A final leg will have to focus on documenting and preserving enough evidence to satisfy regulatory scrutiny and possible investor litigation over the incident and the determination several years down the road.

While some scenarios seem pretty clear-cut, others are more complicated. For example, assume a threat actor posts on a dark web forum (one such as “industrial spy”), stating they have a large dump of sensitive documents from a registered firm named “A.” The threat actor intends to sell the data to the highest bidder or individual files for a lesser amount and posts a small “proof pack” of data. “A” has no indications of a current data breach and initiates an investigation. “A” has no insight as to what else the threat actor may or may not have, its materiality, its source or even the legitimacy of the threat actor. The data posted could be from internal sources or even a key supply-chain partner. Nonetheless, it is a disclosure scenario specifically mentioned in the proposed rules. “A” spins up its internal incident response team and gets outside legal counsel involved. The mention on the dark web forum will likely attract attention in the press. Is the deadline clock ticking? Is it real extortion or a bluff? Does “A” have to buy access to see what the threat actor actually has to be able to make a timely materiality determination? Will the SEC criticize “A’s” decision and make it an example? What would you do? How did you document your decision? It’s a difficult call.

The point here is the need to closely examine your current incident response program, especially with regard to the examples presented by the regulators. Your program needs to be updated and modified to fit the new definitions and initial/on-going disclosure obligations. Do you need additional help in making materiality decisions, performing prompt technical investigations, or preparing disclosures? If so, you must establish those relationships to be able to act in the timeline prescribed. Further, rehearsing various scenarios and mapping out responses will help you in the response.

With the SEC’s new cyber disclosure rules now on the near-term horizon, the time to act is now.

References

i See TSC Industries, Inc. v. Northway, Inc., 426 U.S. 438, 449 (1976); Basic, Inc. v. Levinson, 485 U.S. 224, 232 (1988) and Matrixx Initiatives, Inc. v. Siracusano, 563 U.S. 27 (2011).

ii See Securities and Exchange Commission [Release Nos. 33-11038; 34-94382; IC-34529; File No. S7-09-22], Proposed Rule for Cybersecurity Risk Management, Strategy, Governance, and Incident Disclosure

iii See S.3600 – 117th Congress (2021-2022) – Strengthening American Cybersecurity Act of 2022.

This material is intended for general educational purposes only, and should not be relied upon for any other purpose. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors alone and should not be attributed to HKA Global, Inc., PacketWatch, or any of their employees.

This publication presents the views, thoughts or opinions of the author and not necessarily those of HKA. Whilst we take every care to ensure the accuracy of this information at the time of publication, the content is not intended to deal with all aspects of the subject referred to, should not be relied upon and does not constitute advice of any kind. This publication is protected by copyright © 2024 HKA Global Ltd.